Why password meters lie (and re-used 'strong' passwords are a security killer)

When setting up a new online account, we are all confronted with the frustrating exercise of generating a password. Even more frustrating is the "password critic" we often encounter at the point of account creation - the password strength meter.

(This story originally ran at Insedia.com. Read it there.)

If you are like most people, your initial attempts are often insulted as "mediocre" or "weak." One could imagine the meter speaking with Donald Trump's voice, deriding your efforts.

What comes next is a boon for hackers everywhere -- "password" becomes "password!" or "Password!" or even "Passw0rd!" Hooray! Weak has suddenly become strong! You pass the test; you get the keys, and are allowed to order socks or pay your bills or access company documents.

This, of course, is a kabuki dance that does little to protect digital assets from the prying eyes of criminals. Turns out, they know how to add exclamation points at the end of passwords, too!

The folks at Insedia have access to a database of approximately 4 billion records. Browsing it is, to say the least, an amazing education. I'll be writing a series of stories about it during the next few months.

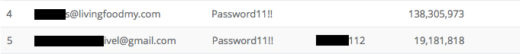

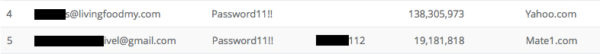

Looking at the data, it's pretty easy to see the habits strength meters have pushed on people. One of the first patterns you see looks like this password ‘evolution'

The password 'progression.'

Creating bad passwords that satisfy password meters is a perfectly logical, predictable strategy used by consumers who are just trying to do whatever it is they have to do. It's behavioral econ 101. Websites nudge them to make bad Passw0rds!, so they use them.

Password meters don't really measure what we wish they did -- how hard will this password be to hack? Instead, they measure how well the password creator is obeying the meter's rules -- how many special characters are used, or how many upper and lower case letters, that kind of thing.

This is not a new problem. Mark Stockley at Sophos Naked Security blog has written several times about the issue. In 2015, he tested five terrible passwords on a variety of meters -- passwords that were all in a now-famous list of the 10,000 most common passwords, like abc123, iloveyou!, or ncc1701 (the Star Trek Enterprise). Most meters rated them as good to mediocre. He repeated the test last year, with much the same result. If you wanted a password that was really going to keep your accounts secure use a totally random sequence of characters similar to ho2mu3vi5ne8lo9ne4ru98 so they don't look like a word or phrase of other sort to improve the security of your data.

In a piece titled “Why you STILL can’t trust password meters,” he skewers them.

“(A hacker’s) first line of attack is likely to be based on dictionary words and rules that mimic the common tricks we use to di5gu!se th3m,” he wrote. “The trouble is that most password strength meters don’t actually measure password strength at all…The only good way to measure the strength of a password is to try and crack it – a serious and seriously time consuming business that requires specialist software and expensive hardware.”

Of course, it’s easy to be a critic or these password critics, but a better question to ponder is this: Do password meters help or hurt? Surely, if they force people to avoid using simple dictionary words who might otherwise do so, that’s a net positive.

Still, there are better ways. In a refreshingly simple, non-techno-babble piece of advice, security guru Bruce Schneier often suggests that consumers come up with a very, very hard password – with many random characters – and then store it in a piece of paper in their wallet or purse. While “never write down your password” is considered Gospel, it’s incorrect, he argues. Security is all about improving the odds. You’re better off with a real strong password on a piece of paper than a weak one that you can remember easily. People store important documents in their wallets all the time. It’s a pretty well-evolved system.

A related question is: How often should you change your password? Enforced password changes are another reason for the progressions that’s are obvious in the Insedia data – Password1..Password2….Password3…..etc.

I recently asked a set of security pros recently how often they change their passwords, and their answers might surprise you.

“I only change my password if I’m worried a service has been hacked/compromised”

“Depends. For your corporate network account? Several times a year. For an online newspaper that requires registration in order to read it? Never.”

“This is not (an easy question) … because also changing the password too often can become a security risk.”

Making, and keeping, good passwords is hard. If you just don’t have any time to deal with password rules, at least familiarize yourself with the most common, and avoid them. Since so many people don’t even take this most basic step, you’ll actually be quite a bit safer. Much safer than people Mark Burnett wrote about here. Using his set of stolen passwords, he found that:

0.5% of users have the password password;

0.4% have the passwords password or 123456;

0.9% have the passwords password, 123456 or 12345678;

1.6% have a password from the top 10 passwords

4.4% have a password from the top 100 passwords

9.7% have a password from the top 500 passwords

13.2% have a password from the top 1,000 passwords

30% have a password from the top 10,000 passwords

Follow this story: AlertMe

If you've read this far, perhaps you'd like to support what I do. That's easy. Buy something from my NEW LIBRARY AND E-COMMERCE PAGE, Sign up for my free email list, click on an advertisement, or just share the story.