If Trump really wants to, can he use DOJ to find the op-ed writer? Snowden might say, 'Yes'

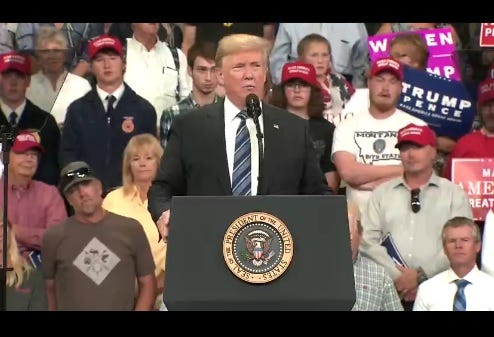

How did the anonymous op-ed writer communicate with The New York Times, and how is the Times working to keep the identity of that person a secret? I posed this question to computer security friends recently as an academic exercise, but it's not academic now. President Trump appeared on Friday to call for a Justice Department investigation in the author's identity.

"Jeff (Sessons) should be investigating who the author of that piece was, because I really believe it’s national security," Trump told reporters on Air Force One, according to NBC News. He also said he wanted the Justice Department to "take a look at what he had, what he gave, what he's talking about — also where he is right now."

As is normal, the Justice Department refused to confirm or deny the existence of any investigation.

It's important to note that Trump invoked national security, and to remember that, thanks to all the lessons learned via Edward Snowden, the executive branch has a lot of tools at its disposal to hunt for the op-ed author. Potentially, investigators could examine all manner of digital breadcrumbs left by the writer, or New York Times employees who interacted with the writer. These might include email headers, telephone call records, instant message contacts, lists of IP addresses, Google searches, and federal building surveillance videos. When searching government-owned devices, much of that could be accomplished without a court order. Should Trump-led investigators take additional legal steps, they could wiretap journalists' telephones, search federal employees' home and family computers. Most extreme, they could drag Times' journalists before a grand jury and demand revelation of the source under threat of prison. (This has actually happened to me; it's very uncomfortable).

To sort through the legalities and talk through practical options, I contacted Mark Rasch, former head of the Department of Justice' Computer Crime Unit. He led several investigations into leakers when working at Justice in a foreign counterintelligence unit.

The first question to ask: How did the source contact the Times? Email, phone call, person to person visit? All these can be uncovered, if the source was not careful.

To begin, FBI investigators could easily examine government-issued computers and cell phones, looking for signs of calls to the Times' offices. That would be unlikely to yield anything, unless the source was very sloppy. The FBI could also use an administrative subpoena to obtain calling records from personal phones of federal employees, and use the same tool to review instant message and email headers, looking perhaps for a flurry of recent calls to the Times.

"Still, they would catch only idiots," Rasch said.

Next, investigators would look at government-owned surveillance cameras that might be trained on New York Times offices in Washington and look for familiar faces going in and out of the building.

There are plenty of other cameras near the Times' office too. The FBI could get private video with a court order; perhaps an administrative subpoena, as opposed to a search warrant, which would require a more stringent judicial review. Should a private firm balk at a request, the FBI could issue a national security letter, forcing the firm to comply and keep the request a secret.

Reviewing weeks of video would be labor intensive, however. Perhaps more productive would be a review of cell phone location data, to see if any employee had been in the Times' offices. The Supreme Court recently ruled that users have an expectation of privacy for location data, so obtaining it would probably require a search warrant.

Still, it seems likely that the source probably already had a relationship with someone at Times, so an in-person visit wouldn't be necessary. On the other hand, were the op-ed delivered remotely, it would seem hard to conduct this kind of transaction without leaving any digital breadcrumbs. Depending how hard the Trump administration wants to work, it could employ tactics that would be menacing to the Times and to journalists. The FBI could ask the Times' Internet Service provider for a list of IP addresses that hit its "contact" page, for example. By invoking national security, the agency could issue a national security letter, which would force ISPs to comply and keep the request a secret.

Or, the FBI could perhaps work with the NSA to search a database of Internet traffic that it has already vacuumed up, using a tool like XKeyscore, revealed by Snowden. Doing so might require a so-called 702 court order, and proving to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act court that the issue involved national security and the potential of a foreign actor. While this seems unlikely, Trump's raising of foreign powers in his Friday statement seems to leave the door open to the use of such an investigative tool

The FBI could also demand private emails from webmail providers via court orders.

The Times, like many publications, has tools for sources to deliver documents anonymously. It has a SecureDrop site, for example. But Times employees no doubt discussed publication of the op-ed. If one such discussion occurred on email, that could be demanded via court order. Anyone in possession of the email -- the Times itself, its ISP, or a third-party email provider -- could be liable to cough up the email.

All of these investigative techniques would be of little use in a wide dragnet, Rasch cautioned -- but if the White House had a narrow list of 10 or so suspects, they might be effective finding the source of the op-ed. A message that was composed on a computer would likely leave traces on that computer, he said, so a search of 10 administration employees' homes and family computers could expose the writer.

Should the administration attempt such a search, Rasch said, he'd hope the target group would quit en masse.

Still, a broad fishing expedition like this often yields no results, Rasch said, until the suspect list is narrowed to one.

"Ultimately, such searches are not really useful in finding out who did something like this. They are more useful in proving a suspect did it, once you have a pretty good idea who it is," he said.

Even still, with years of experience and a wide set of investigative tools at his disposal, Rasch has a word of caution for leak investigators.

"We almost never found the leakers. You rarely do. Only if it's a continuing leak," he said.

So, stay tuned.

ORDER THE NEW EDITION OF GOTCHA CAPITALISM NOW! (Print edition also available)